Grief is perhaps the most brutal of emotions. Not because it is more intense than others. Certainly fear can be more immediately overwhelming. But Grief is a chronic state. It is a response to Loss. Not simply the loss of a wallet, or a set of keys, but something irreplaceable and irretrievable. The object of that Loss is usually, though not always, the death of a living and loved soul. While anger, as an example, is

explosive, Grief is implosive. It digs its nails into your very surroundings, the air you breathe, then into your skin and pulls every scrap of being to a point in your core that is the seat of your self. It is a reaction to tragedy that is ripping in its intensity. It crams the self into a space so dense that you cannot help but be sucked in. The question then becomes, can you crawl out? The answer is yes. But it will draw on all of your emotional and intellectual resources. It will make you reach back and grope for strength in your personal history. It will challenge you and reshape your

beliefs about the world and about yourself.

My wife, Linda, and I, after ten futile years, were within ten days of giving birth to a daughter. Then catastrophe struck.

The noun ‘catastrophe’ does not say too much, it says too little. Our daughter Katherine suffered a birth

accident that left her cortically blind and deaf, wracked with seizures from hightone low-tone cerebral palsy and unable to suck or swallow. Dependent for nourishment on a small plastic tube inserted into her stomach. Oh we’d wanted very much to raise a child. But the deep Grief was not for our loss of a child, but her loss of the opportunity to paint her story onto the canvas of life.

Katherine died at the age of seven months. The spaces that filled her brain, left by tissue that had been starved of oxygen and had died, filled with dense spinal fluid and simply became more than her brainstem, seat of the autonomic functions, could

bear. Her heart just stopped. But ours did not. We had to live. But how? First was to find an answer to the question ‘why?’ For us we found an answer in the words of an ancient Asian sage, Lao-Tse:

‘Nature does not play favorites. She regards her creations without sentimentality.’

Others seek comfort in God, some unfortunately in drugs and alcohol. But there is no good answer to the question, ‘why?’, and Linda and I had to get in synch emotionally. Grieving is differential. Highs, if

there are any, usually are just a brief respite; and lows rarely are coincident in time. People grieve, as people walk, at their own pace. Linda sat up every night while Katie was alive and poured her heart and her guts out in a flood of tears. I had simply been ‘dad’. But after Katherine died it was time for me to start to comb through the catastrophe for some meaning. Linda was ahead of me and because of love she waited patiently for me to catch up. Understand, the pain never goes away completely. Ever. But our stoic view has helped us. That and, surprisingly, black

humor. Some of us need bluebirds and some of us like blackbirds, I guess.

Linda and I had taken Katie to a school for blind children in Denver, infant to pre-school. Since

she was so terribly compromised, the therapy there and at home probably did us more good than it did her. We massaged her tortured muscles and sat in a dark room while colored lights blinked away on a little device.

Then, after Katie died, Linda took her considerable financial skills from a career on Wall Street and poured them into the school, the Anchor Center for the Blind. I’d like to think her effort, over fifteen years, did some good. I, instead, had a flash of inspiration. I decided to write a story. The short story became a long novel that eventually became a series of novels, The Ur Legend. I gave my daughter a life in them that she’d been robbed of. Of course, they were fantasy, so I could actually give her life on the page. That’s the beauty of fantasy. One can fashion make-believe and make it believable.

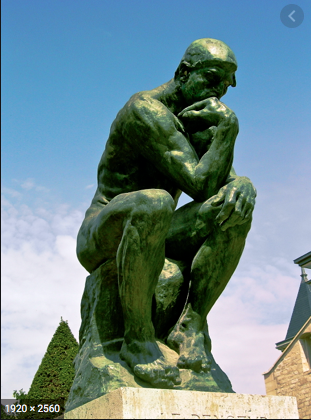

So the question becomes, can art be a balm for Grief and if so how? There are countless instances of art dealing with the subject of grief. Sculpture: the Pieta and a mother’s outpouring of not only grief but also love into the dead body of her son, in a gesture of pure ‘agape’, unconditional love. Plays: Trojan Women by Euripedes, exploring the grief of women who have lost sons, husbands and their home; Grief in bitter resignation. Books: the Mockingjay series, Grief transformed into action. And Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Grief shaped by love. Poetry: Galway Kinnel’s ‘Neverland’, Grief expressed as helplessness.

An English teacher of mine in high school wisely noted that there is no ‘correct’ interpretation of a work of literature, or of any work of art, for that matter, because there is the artist’s intent and the inferences made by the audience. Both are valid.

In my art, my books, Grief was softened joy. The joy of fashioning a life out of words. I am still astounded, when I read certain passages of Sun Valley Moon Mountains, what a special person ‘my daughter’ Ur is. And I am even more moved by her as a young woman in The Girl from Ipanema. I write with an old fashioned fountain pen because it moves effortlessly across the paper, never tiring my hand, as my mind pours out thoughts that are soaked in ink as the nib glides across the page.

But what of my audience? What’s in it for them? As much as I have wanted to create another life for Katie, I’ve also tried to show people, especially those who can empathize with our Grief, that there is an other way of viewing the tragedy as a function of a universe that is not malevolent, nor even cold, but simply a universe that ‘is’. The ‘why?’ of it all need not be an instrument of torture.

So my advice to those who are members of our grisly club is to stop asking ‘why?’, because there is no satisfying answer but to pick up a brush and some paints and a canvas, or a piece of chalk, or a lump of clay, or a pen. Or open an Excel spreadsheet, as Linda did. As Achilles said to Priam, who came seeking the body of his son, Hector, in the Iliad, “we…old man must eat”, for the living, as much as they grieve their loss, must still get on with the business of living.