Note from Ajax Minor: This short story was published with permission. It was written by my sister, Joanne Sinsar Trebbe.

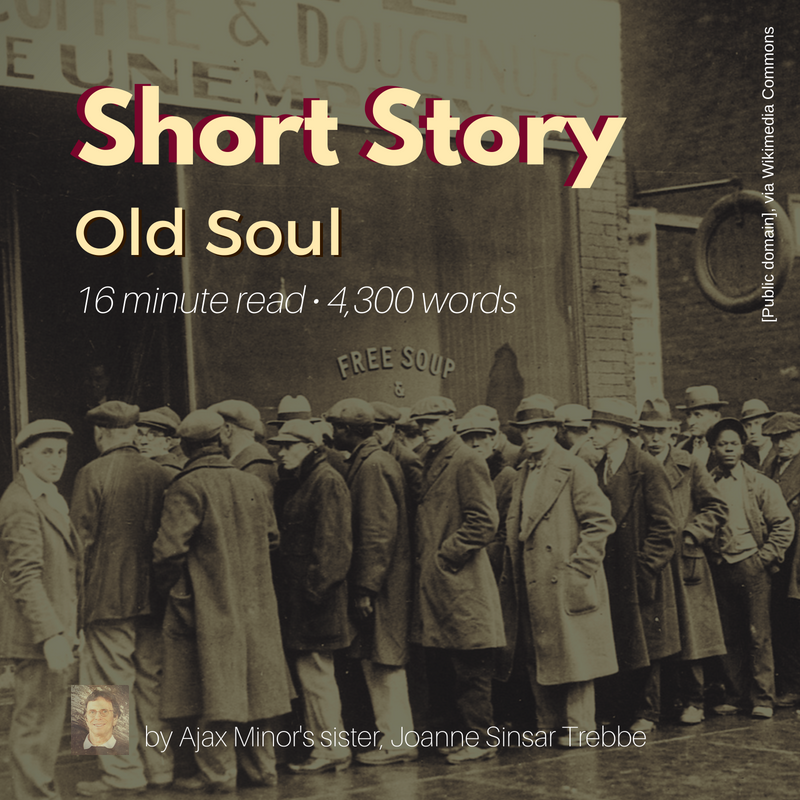

I was ten years old in 1936, when the economies of the world were drowning in the Great Depression. The winds of war were beginning to blow across Europe, yet our continent was still isolated from the coming storm.

I was ten years old in 1936, when the economies of the world were drowning in the Great Depression. The winds of war were beginning to blow across Europe, yet our continent was still isolated from the coming storm.

One frigid January day, in the early morning hours before we had awakened, a day I would revisit in my mind countless times in years to come, my mother composed a grocery list for her weekly trip to the local food market. It was always an outing that filled her with eagerness, as well angst. Feeding a family of nine in a time of rampant, worldwide poverty took guts and ingenuity. She possessed both.

On market days, my mother would enlist either my little sister, or me, to tag along and help her lug the ragged cloth bags laden with precious staples back to our low rent house, the only place I had ever called home. We would each vie for the chance to join her on the short two block journey, even though it felt like miles to the abbreviated legs of a young child weighted down by bags full of supplies. But the possibility of a penny candy, or two, from the great glass jar upon the grocers counter, stuffed to the brim with forbidden treats, was well worth the arduous, uphill return trek home.

Although I was only three years older than my baby sister, her whining pleas were usually trumped by my age and strength. We were the youngest girls, the last two surprise gifts, in a family already burdened by five hungry mouths to feed. My parents had begotten seven children, not one planned, but all cherished. My mother always said, in a matter of fact fashion, she had had too many children, amending her frank confession with the admission that she could not imagine life without them. And while the Depression had left so many with so few material necessities, the one commodity most people did not lack was children. Unfortunately, in a world already overburdened by high rates of unemployment and endless bread lines, a large family was a luxury not many could afford.

On that particular January day, our part of the world was deep in winter’s icy clutches. The unrelenting winds whipped frozen, dead leaves around our tiny front yard, the last vestiges of fall pirouetting over the frozen earth. Great gusts tirelessly battered the frost etched windows of our sparsely furnished living room, creating eerie whistles that found their way up the winding staircase, creeping into the chilly corners of our little bedroom, sending shivers up my spine.

I lay in my bed, waiting for the fog of sleep to lift as I burrowed deeper into the threadbare blanket. Sometime in the early morning hours, my mother had silently slipped into our room, and covered my sister and me with our worn little winter coats in a fruitless effort to keep us warm in the unforgiving cold of a house unheated.

I peaked out from underneath my sleep filled eyelids and instantly felt the icy air claw at my eyes. The tears began to well up, then seeped into the sleep caked tear ducts, overflowed, tumbled down my chilled cheeks, and threatened to freeze into tiny ice chips before my tongue could taste their salty dew.

Next to me I felt my sister begin to stir. We shared a small, lumpy mattress on a full size, rusty metal box spring bed. Having a bed of my own to sleep in was beyond my comprehension.

I sucked in a deep breath, the moist air felt like ice crystals as it seized up my lungs. I jumped out of bed and held back a scream of shock when my feet hit the unforgiving, glacial floorboards. Teeth chattering, I quickly dressed into a faded frock. My fingers were quivering and numb as I clumsily fumbled with the small wooden buttons. I pulled on a pair of saggy woolen tights, and scooped my winter coat up off the bed in hopes of needing it later.

I hurried my shivering body downstairs to the only source of heat in the entire house. An ancient, cast iron, wood burning stove sat, Buddha-like, in the center of the kitchen where my family often huddled together during the long months of winter. We were hypnotized by the crackling sounds it spat from its fiery belly, as we worshipped its small gift of warmth.

I dropped my coat on the wooden bench in the downstairs hallway, and followed the rich aroma of freshly brewed coffee into the kitchen. My mother was already standing watch over a large, dented old pot bubbling with gelatinous oatmeal. Her day had begun hours before, shoulders hunched, succumbing to the weight of another tedious day of minutiae. She received no accolades for her valiant domestic efforts.

My mother struggled each day to stretch the food from a sparse larder into meals that would fill the hungry bellies of seven children. She toiled washing endless loads of dirty laundry, a backbreaking chore that required strength and stamina. I saw her bent over a manual washtub countless times throughout my childhood. She scrubbed piles of mended hand me downs, up and down the washboard, strong, steady strokes, until her chapped hands cracked and bled. On warm, sunny days she hung piles of sopping clothes on a makeshift clothesline in the backyard. In the colder months, she still insisted on hanging them out in the fresh air. Then, she would gather in each piece of clothing, frozen stiff as a board, and painstakingly drape them on every available chair and countertop in the kitchen to slowly dry in the meager warmth that spewed from the wood burning stove.

She lived her life without complaint. Her creed, “It’s a great world, if you don’t weaken.” She was not a martyr, but a woman who had accepted life as a challenge, one she met head on and without expectation, until her last breath.

Three of my brothers and my older sister were already out of the house and off to work that morning. In the old days, especially during the Great Depression, as I often reminded my own children in years to come, everyone labored and contributed to the family coffer. Although my oldest brother was in college on a full academic scholarship, the golden boy of the family and my parents’ pride, my older sister worked full time in an ice cream factory, a job no one envied in the frozen months of winter. My other three brothers worked in the hat factories, our town’s claim to fame in those days, when men and women weren’t considered descent in public without a proper hat. The truth was that the hat factories were financial saviors to many of our town’s people in a time when jobs were scarce in most cities across our country.

I quietly sat down at the long, knotty pine table that had seen one too many years of use, but still valiantly groaned under the weight of countless more meals. My mother turned around, pot and ladle in hand, and gave me a fleeting smile that warmed my spirit more swiftly than the glowing embers in the old stove. But her expression rapidly changed. A look of distraction furrowed her brows, as her mind began to compartmentalize the endless list of chores that would consume her day.

She shuffled over on weary legs, and scooped a big dollop of the bland gruel into my chipped bowl of gray colored Fiestaware. I stared at it with the usual suspicion of a child. She saw my disdain, rolled her eyes, and reached across the table to an unopened bottle of milk. It was clear glass, the way milk used to be sold, before the modern days of mass produced, plastic containers. She removed the paper cap and carefully poured the treasured cream, accumulated at the top, onto the plain oatmeal. Immediately it was transformed into a meal of luscious, creamy sustenance. To my delight, she added a sprinkle of brown sugar. I quickly tucked into my breakfast with vigor.

My sister skipped into the kitchen, always the happy little sprite, tittering like a church mouse about the dreams she had had all night, real or imagined. At the same time, the back door burst open, letting in an unwelcome blast of winter’s wraith, and carrying along with it my poor, exhausted father, nearly frostbitten from working a long nightshift in the bitter cold. He was a lineman, and sometimes engineer, on the local railroad that carried passengers and freight back and forth to the nearest big city. We lived within walking distance of the railroad station, so my father could easily get to work on foot. In those days, driving a car to commute to work was an unimaginable extravagance.

“Sit down,” my mother clipped to my sister, in her low, stern voice, as she served up another healthy portion of oatmeal to her youngest child, then quickly attended to her husband.

My father was a short, stocky man with views on life as solid as his frame. He had come to this country from Wales to escape a life working in perpetual night, slaving underground in the coal mines deeply embedded in the hills of his homeland. He had been an asthmatic child and facing the fate of a coal miner would have surely been a death sentence. So at the tender age of sixteen, he boarded a freighter to a new life with relatives in America.

His first job was as a milk deliveryman peddling his wares in an old wooden cart pulled by two dappled gray nags, prime candidates for the glue factory. One day while working his route, he saw a beautiful girl standing in her front yard filling a large metal pail with water from a pump. He was struck with cupid’s arrow and knew that she was his destiny.

My father limped in on frozen legs, his bones as fragile as the icicles dripping from the eaves on our roof. My mother hastily dragged a kitchen chair across the floor, its legs screeching in protest, and set it next to the melting warmth of the wood stove. He lowered his aching body into the chair and heaved a great sigh. She lifted one of his stiff legs and carefully straightened the brittle muscles. Then, she gripped his frosty boot, the worn soles so dotted with holes they resembled Swiss cheese, and yanked and pulled, until his foot finally released its tattered leather into her strong, sturdy hands. She dropped the grimy shoe unceremoniously onto the old wood floor where it landed with a solid thud. The kitchen grew quiet with only the sounds of his laborious breathing, and the gentle scraping sound of metal on metal, as my mother gave the last portion of hot, steaming cereal to my half frozen father. In my innocence, I was oblivious to the secret look my parents exchanged that could have thawed a glacier.

My sister and I finished our breakfasts and hurriedly cleared our places at the table. We scrambled upstairs, pushing and shoving each other in an attempt to see who would reach the only bathroom in the house first. Of course, I always won that battle, my age and size once again usurping her gallant effort to win something, anything, over me.

I carefully washed my face with a raggedy old washcloth and the last sliver of an Ivory soap bar. I forgot to brush my teeth, an action I would regret many times, years hence. After a few minutes of idle primping in front of the mirror, I finally relented to my sister’s incessant pounding on the bathroom door. I jerked it open so energetically, she toppled, face first, onto the unyielding, tile floor.

I knew my effort to antagonize her had been too great when she burst into a fit of tears. I spent the next few minutes trying to mollify her. If my mother overheard us, we would both face certain punishment. She finally calmed down, but not before accepting my bribe of an extra dessert that evening. Mine of course.

My mother shouted up the stairs for me to hurry. She announced that I was to accompany her that day. In the excitement of our little scuffle, we had all but forgotten that it was market day. I raced downstairs with my sister trailing close behind, tantrum reignited, screaming loud protests in her favor.

My mother was not in the mood that day to deal with our usual debate over who would make the trip with her. When we reached the hallway she was standing in her Sunday coat, a garment that had seen better days. She had been absentmindedly pulling on her white gloves, one finger at a time, when she glanced down at us. The look she leveled on us was one reserved for those times when her last bit of patience was hanging on by a mere thread. My sister wisely opted to keep her objections to herself that morning. She shot me one last scorching look, stuck out her tongue and spun on her little heels. She sauntered into the kitchen where my father, an easy touch to her charms, sat silently defrosting in front of the stove.

I swiftly grabbed my winter coat from the wooden bench. The coat was a depleted hand me down from my older sister, gray wool with frayed sleeves and mismatching buttons. I shoved my hand into the left pocket where my fingertips gently stroked the two copper pennies I had saved for my next trip to the market. It was the Depression, and two cents to a child was a fortune. I then reached into the right pocket of my coat, pulled out my hand knitted, red mittens, and carefully eased them over my small, chapped hands so the yarn would not catch on little dried pieces of skin.

My mother handed me several of the old cloth bags, then turned the glass doorknob of the heavy oak front door, and with the help of the wind, pulled it open. Instantly we were assaulted by a blast of bitter air, so harsh it took our breaths away. My mother stepped out into the cold, as I wrestled with the big door to close it. For a moment I thought the door might win the struggle, but it finally gave way and slammed shut.

Skipping to catch up to my mother, I didn’t worry about stepping on the cracks or lines in the sidewalk, something my sister and I usually took great care to avoid. We didn’t meander along the way as we would have in the warmer months, taking our time to admire our neighbor’s flower gardens, or pet the mangy old mutt that hung around our street and belonged to no one in particular. Instead we hunkered down, heads bent, eyes downcast, to brace ourselves from the north wind’s chilling onslaught and forged ahead. She reached down and grasped my little hand in hers and squeezed it tightly in a vise of bones and sinew, strong from many years of hard labor. The two blocks to the market were all downhill along the uneven sidewalk, so we thankfully arrived at our destination in a few minutes time.

The grocery store was a family owned establishment, like most markets in the old days. It was on the first floor of a rented building. The grocer’s family dwelling was above it on the second floor.

My mother turned the tarnished door knob in her white-gloved hand and tugged, with considerable strength, against the negative force of the wind. The door surrendered and swung open. A tinkling brass bell attached to the door and doorway announced our arrival.

Once inside I was immediately transported into a world filled with familiar and tempting sights and smells. High tin ceilings, creaky, unfinished wooden floors, and the usual staples of dried and canned goods were stacked on high shelves, behind the grocer’s main counter. To the left of the main shelves was a large, walk in refrigerator with a constant, cold temperature to keep meat and other perishables safe.

There were several free standing shelves in the middle of the store, stocked with various groceries and sundries. A large wooden barrel chock full of sour pickles stood in a corner near the front window. Just the sight of it made my mouth pucker. Spices from far away lands filled the air with the mystery of their exotic scents.

But I was not concerned with any of those boring items that made our everyday lives possible. What captivated my total attention was the huge, glass jar silently beckoning me from its sacred spot, high up on the main countertop. Inside that jar held the promise of innumerable confectionary delights, placed there solely for my consumption.

I headed for the counter, trying to appear casual in my demeanor, inconspicuous, not wanting to seem greedy and gluttonous. My mother would never have tolerated such behavior from one of her daughters. We may have been poor, but she instilled dignity and pride in all her children.

I edged ever so closely to the dearly coveted prize. My mother chatted with the grocer about things I barely understood. The Depression, The New Deal, unemployment, Hitler, all just words to me, familiar, but without substantial meaning. She looked at me from the corner of her eye and I watched her lips begin to turn up at the corners, the hint of a smile that never really reached her eyes in those difficult days. It was the same unspoken message that passed between us each time we stood at that very spot, my mother acutely aware of my agenda.

“I think my daughter has some business she’d like to conduct with you,” she said, feigning a very businesslike tone to the grocer. He was always delighted to oblige my mother and indulge me in our little game.

He glanced at me, slightly bowed his head, and lifted the heavy lid off the jar of treats. My mouth began to water in anticipation. With great theatricality, he reached into the treasure trove of treats and presented me with two, succulent peppermint sticks. I carefully handed him my two precious pennies, now clutched tightly in my hand, in exchange for the candies that would soon be melting on my tongue, their strong mint fragrance tickling my nostrils in the most delectable way.

I held the peppermint sticks wrapped in thin paper, dragging out the sweet anticipation of the moment. Then, ever so carefully, I slowly unwrapped one of my prizes, carried it up to my mouth and placed the end of it on the tip my tongue. I closed my eyes in rapture.

But my reverie was short, abruptly broken by the tinkling of the door bell, followed by a blast of stinging, chilled air, instantly bringing me back to reality. Out of basic human curiosity, I turned and looked to see if the new customers were anyone we knew.

My eyes fell upon an unfamiliar young woman whose face bore the lines of hardship and sorrow. But it wasn’t she who held my interest. Standing next to her was a little girl with blonde hair hanging in tangled ropes about her face. I still can’t remember the color of her eyes, but it was the intensity of those eyes that made my feet take root to the floor, unable to move. I sensed that behind those eyes, liquid orbs of emotions lived a very old soul.

Her mother moved forward, toward us, and the little girl followed. I suddenly realized that something was odd about her gait. It was when I glanced down at her legs that I saw it. A cumbersome brace wrapped around a tiny, withered limb. She dragged the imprisoned leg behind her, like a ball and chain.

My mother surreptitiously tapped my shoulder and broke the spell. It was at that moment when I realized I teetered upon one of life’s great precipices. Watching the little girl struggle to walk with such conviction and purpose, I knew that I would never again see the world with the innocence a child.

The sweet, sharp flavor of peppermint turned to sawdust in my mouth. A large lump formed in my throat, my mouth was dry as a desert’s baked sands. Suddenly, I became shamefully aware of the peppermint sticks grasped guiltily in my hand, tangible evidence of my selfish desire. I rewrapped the opened candy and placed it in my undeserving pocket.

How would I ever reconcile such childish indulgence after seeing life’s cruelty in that little girl’s leg? Yet, when I looked at her, I had the realization that she bore no bitterness toward life for her fate. As she smiled shyly at something the grocer was saying to her, I felt my small, insulated world tilt on its axis. This was a turning point in my young life.

I was overwhelmed by more feelings, foreign, yet somehow vaguely familiar. And then it hit me. Gratitude. Humility. I was grateful that I had two strong, healthy legs. I was humbled by her grace in the face of adversity. I knew I could do nothing to change the little’s girl’s lot in life. But somehow I wanted to let her know I understood that all she wanted was to be accepted and not judged by her imperfection, but by the person that she was inside. It wasn’t her twisted leg, held captive by a metal brace that would carry her to an unknown destiny, but her strength of character.

My mother had finished her shopping and was about to hand me two of the lighter bags stuffed with groceries. I looked up at her with pleading eyes. Always a wise woman, she understood what I was asking. She nodded her head and waited.

I took a deep breath, and walked over to the little girl. She looked at me, chin up, her face open with trust and kindness, and something more. Courage. I was humbled by her strength. I sensed that this little girl was proud and any offer of charity would have been the greatest of insults. A chip would find no solace on her shoulder.

Neither of us said a word, we simply communicated in the universal language of children. I handed her the unopened peppermint stick without hesitation, something I had never even done for my own little sister. Her face lit up with a brilliant smile. She reached out, and then pulled her hand back, looking up at her mother for reassurance. Her mother grinned and nodded, yes. Once again, the little girl reached out and this time accepted my tribute to her bravery. She held the peppermint stick in her little hand, almost reverently, for fear it would disappear before her eyes. I quickly turned before she could respond. I did not want any thanks for a simple act of kindness for someone so much more deserving than I. I walked back to my mother as tears threatened once again.

Pride spilled from my mother’s eyes. A special bond was formed between my mother and me that day, even though we never spoke of it again. She handed me the cloth bags and we headed back out into the frigid winter day. I didn’t look back, I didn’t have to. The little girl’s eyes would be imprinted in my mind forever.

Once outside, we began to silently trudge up the hill, back to our safe haven. Right before we reached our house, it began to snow. Fat, thick, crystallized snowflakes fell from low, gray clouds, sticking and clinging everywhere they landed. I stopped and tilted my head up toward the sky and felt the purity and individuality of each flake as it hit my face and melted, cleansed and baptized me. I was overwhelmed with joy, and experienced an awareness within myself that I had been incapable of understanding before that day.

Invigorated by a newfound sense of self, I raced ahead of my mother, and up the front porch stairs, taking them two at a time. Mittened hands pounded the door with muffled blows. With great effort, my sister dragged the front door open with two hands. I floated in, as if on air, set the cloth bags of groceries down, reached into my coat pocket and produced the other, rewrapped peppermint stick.

She watched me cautiously and waited for the usual teasing and boasting to ensue. But there would be no tormenting from me that day. Once again, gratitude washed over me, seeping deep into my pores, not for myself this time, but for my little sister who stood solidly grounded on two, sound and sturdy legs. Her able limbs would carry her through life’s peaks and valleys, an act I would never take for granted again.

I took her little hand in mine, opened each finger, one by one, and gently placed the peppermint stick in her hand. Eyes wide with shock, she stared at me in disbelief, waiting for the other proverbial shoe to drop. But instead, I bent down and hugged her.

Until that day, I had no idea all of the gifts life had bestowed upon me. A simple act of compassion brought on by a handicapped child had created a metamorphosis. In one brief encounter with a little girl, behind whose eyes bore the courage and strength of an old soul, I felt a subtle, significant shift within myself from the girl that I was, to the woman I would be. My journey to adulthood had begun.

THE END

© Joanne Trebbe 2018